The big takeaway from the European Parliament elections: the centre has held, but a trend in far-right gains continues. This means that Europe’s fight against climate change can go on but is faced with a trickier political landscape at a time when big decisions need to be taken. A fair and green industrial / competitiveness deal still looks within reach in the negotiations for the incoming European Commission. However, EU leaders will face a major test on securing enough financing to make it a reality.

This orientation briefing makes sense of the new political order taking shape in Brussels and what it can mean for climate action. We set out what is needed for the next phase of the green transition and what the elections tell us about the EU’s ability to meet these needs.

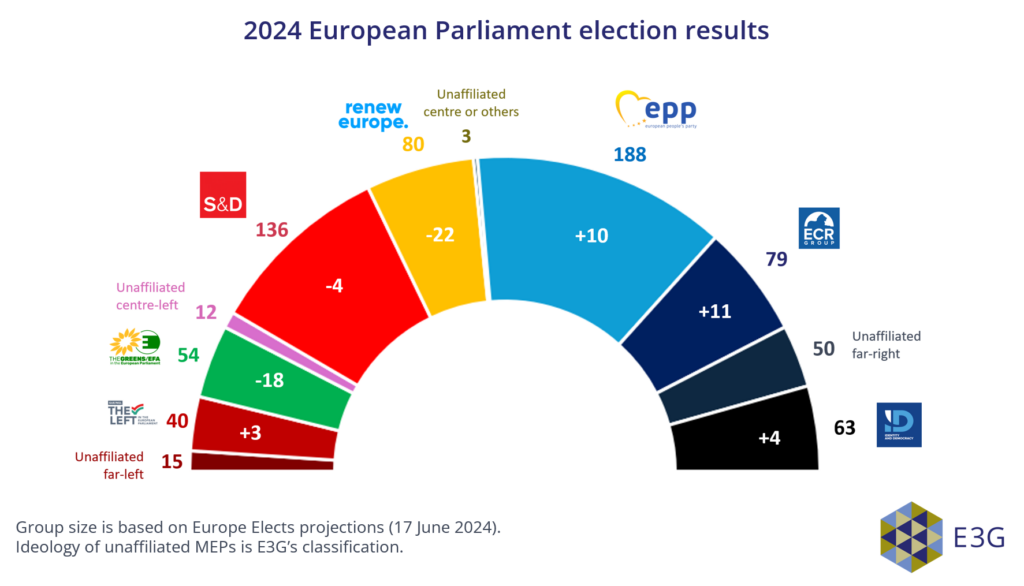

Pro-EU, pro-climate parties still have a majority in parliament

Most Europeans voted for pro-European parties that are committed to Europe’s clean transition. The EPP – the political group of Ursula von der Leyen, whose biggest achievement was the European Green Deal – remains the biggest party. It is expected to turn to its traditional partners to form a coalition: the centre-left S&D and liberal Renew.

But a slimmer centre means a shakier coalition

Liberals and greens sustained the greatest losses in the elections. This means the ability of climate-progressive coalitions to override the EPP should it backtrack (as it has previously done), is severely hampered. Meanwhile, far-right parties – many hostile to climate action – have made the biggest gains.

Commission President hopeful Ursula von der Leyen will have to reach out beyond her usual political partners to form a coalition with a comfortable enough majority to vote her in. She has already made overtures to the far-right ECR. However, her stated intention is to work with “those who are pro-European, pro-Ukraine, and pro-rule of law”. She might find more reliable partners in the Greens.

The direction of travel leaves space for climate action, but with bumps in the road

Severe climate risks and impacts are already affecting economic stability and competitiveness in Europe. Energy security, competitiveness, and stability will remain strong drivers of future climate action. However, the revised make-up of the European Parliament will mean more contentious debates about the pace and types of measures to implement.

Securing climate action in the new political context

The future of EU climate action depends on the bloc’s ability to fulfil five key benchmarks. The achievability of each has been influenced by the elections in different ways. The greatest potential for progress is in securing a fair and green industrial/competitiveness deal, while finding sufficient investment for the transition remains crucial but will be most difficult. Elsewhere, the picture is mixed.

Expand each benchmark below to find out more.

Types of policies needed: Ambitious 2040 target, EGD continuation.

Post-election grade: mixed

Businesses and civil society are united in their call for regulatory predictability. Setting an ambitious, fair and feasible 2040 target can ensure that future policies build on the EGD and create precisely the stable outlook that is being called for.

Notwithstanding the strong majority in support of the European Green Deal in the new parliament, this prospect faces some hazards. The EPP is now responsible for delivering the long-term stability that businesses are strongly calling for, but reliance on far-right groups would bring regulatory uncertainty. With Renew’s leadership uncertain following a loss of French seats, a new cohort of S&D politicians from Italy, Spain and France can try to counterbalance risks posed by the far-right.

Types of policies needed: A pan-European industrial plan supported by adequate new EU-level funding, green lead markets and strong environmental and social conditionalities; integrated infrastructure planning such as grid expansion, electrification and a plan for hydrogen use and gas phase-down.

Post-election grade: has potential

Calls for a European industrial policy to boost competitiveness have emerged loudly from political and expert debates among heads of state, industry, think tanks, and civil society. EU leaders are hence likely to call for an “Industrial” or “Competitiveness” Deal at the upcoming European Councils, to be picked up by the next European Commission.

Having demonstrated his political resilience in the EU elections, Spanish PM Sánchez can call for strong environmental and social conditionalities, something that the S&D at large is demanding.

Types of policies needed: Just Transition Policy Framework; social, including distributional, impact assessments of industrial/strategic projects; bolstered social protection, access to quality public services, funding bump for the Social Climate Fund and Just Transition Fund and environmental and social conditionalities tied to public funding; code of conduct for stakeholder participation.

Post-election grade: mixed

With concerns about the cost of living remaining a top issue for many voters, all parties made “leaving no one behind” central to their campaigns, including the far-right. However, the latter has an appalling record on workers’ rights and social issues.

This is an opportunity for the EPP to translate its campaign pledges into a tangible reality by making the transition ahead a source of optimism rather than fear for the many Europeans who voted them into power. This requires a shift in the approach to just transition from narrow compensation for lost carbon-intensive jobs to a broader approach ensuring all affected stakeholders have a fair share and say in the transition.

Types of policies needed: Fresh EU-level money, single transition plan for companies, green public procurement, fossil subsidies phase-out.

Post-election grade: deadlock

Investment is the critical enabling thread that runs through every other benchmark outlined here, and the EU’s funding gap has been well documented. Yet this scale of importance is matched by an almost equal level of deadlock and competing demands at EU-level.

The EU election doesn’t fundamentally shift this. French President Macron’s likely preoccupation with his national campaign will mean that a formerly strong voice for advancing the debate will be comparatively weaker. Securing a deal on finance will be a major test for the next European Council President.

Types of policies needed: Partnerships with G20 countries that seize clean economy opportunities, strengthen human and labour rights, and foster resilience; enhanced clean investments abroad; a credible and ambitious 2035 NDC ahead of COP30; reform of global trade and financial systems to support climate action.

Post-election grade: mixed

The war in Ukraine and persistent geopolitical instability has elevated voters’ concerns about security and the international landscape. But the balance between EU and national action, free markets and protectionism, remains contested.

The increase in far-right policymakers risks a steer towards internal security and curbing immigration at the expense of strengthening the EU’s international leadership and credibility. Pro-European parties have the numbers to course-correct towards an updated global strategy that strengthens key partnerships, boosts the EU’s strategic autonomy, and sets a path towards a stable and climate-safe future for all.

What’s next?

- Parliament will take shape over June and July. The final size of the political groups, and leading national delegations within them, will emerge as MEPs (many currently non-affiliated) join existing or new groups. A reconfiguration of the far-right is possible. The President of the European Parliament and leading committee roles will be chosen at the first plenary session on 15–18 July.

- Leaders will finalise the EU Strategic Agenda. The agenda is due to be adopted, and top positions filled, on 27–28 June. If no agreement is reached, an extraordinary meeting will take place in July.

- The next President of the European Commission will take office. An endorsement vote is expected on 18 July. The nominated candidate must develop priorities aligning with guidance from the European Council, while gaining the support of a majority of newly elected MEPs.

- A new College of Commissioners is established. The Commission President assigns each Commissioner a portfolio and “mission letter” outlining policy tasks for the next five years. Each nominated Commissioner must receive endorsement from their respective European Parliament Committee, allowing MEPs to make specific demands of the Commission. A final vote on the full College takes place in the European Parliament.