Here, we highlight the work of E3G to map the political economy of cooling in a warming world. Sustainable cooling is an integral component of achieving the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, delivering on the Sustainable Development Goals and the UNFCCC Paris Agreement. This work was funded by the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program.

Contents

- E3G Political Economy Mapping Methodology (PEMM)

- National Conditions: what underpins the sustainable cooling transition?

- Political System: who supports a sustainable cooling transition?

- External Projection: how can cooling support foreign policy and climate diplomacy priorities?

- Routes to Impact: what are the multiple pathways to net zero cooling?

- Cool Resources Library

Sustainable cooling is an often overlooked but nonetheless essential part of net zero transition. Cooling emissions – from air conditioning and refrigeration – are estimated to be 10% of human-caused global emissions. This is broken down into direct emissions from refrigerant leakage – mostly F-gases which can have 10,000 times the warming potential of CO2 – and indirect emissions that result from the electricity generated to power cooling equipment and systems. Direct emissions are responsible for 20% of global emissions, while indirect emissions are responsible for the remaining 80%. This means, even with 100% renewable power, cooling equipment dominating the market today will still produce emissions from leakage of high global warming potential refrigerants during operation, maintenance, and disposal. Successful mitigation of emissions from cooling refrigerants alone could reduce future warming by up to 0.4° C up to 2100.

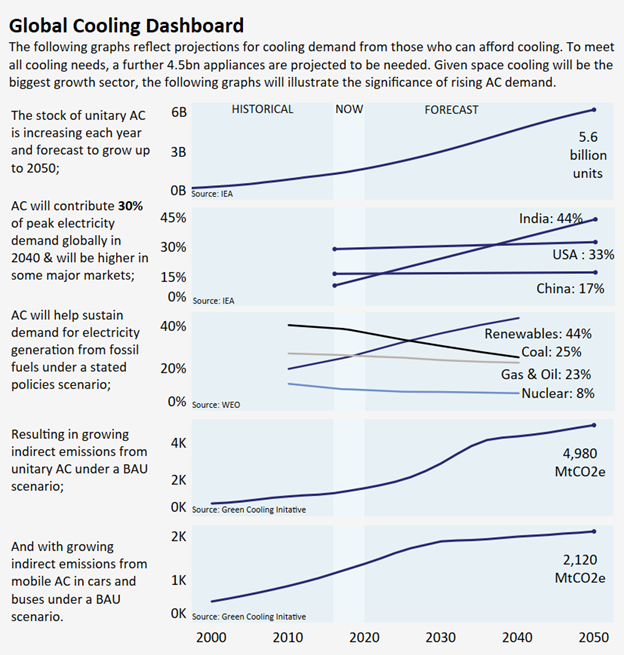

Cooling stresses our energy systems contributing 20% of global electricity demand in buildings and more than 50% of peak demand in hot climates. In 2018, cooling energy load connected to the grid globally surpassed that year’s record–setting additions of solar generation capacity. As temperatures and incomes increase and with record urbanization, cooling’s share of electricity demand is set to rise, second only to electric motors, fuelling the need for more generation capacity and prolonging the life of fossil power plants. According to a 2018 IEA report, demand for space cooling alone could triple to 6,200 TWh/year by 2050 equivalent to all electricity demand in the United States and Germany in 2018.

Cooling is not a luxury. At present, Sustainable Energy for All has identified more than 1 billion people across 54 countries who are at high risk due to their lack of access to cooling. Compounding this, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported that at 1.5°C of warming, 2.3 billion people – more than a quarter of the world’s population – could be highly vulnerable to heat risk. Meeting the needs of those who can afford cooling would see an increase from 3.6bn to 9.5bn appliances in use across space cooling, stationary refrigeration, and mobile cooling sectors by 2050. However, this does not tell the whole story. Meeting everyone’s cooling needs would see a further 4.5bn appliances in use by 2050.

A full spectrum of sustainable cooling solutions is needed. Globally, as climate impacts become more frequent and more intense, more people will be exposed and vulnerable to heat impacts. Alongside the highest efficiency equipment, solutions that avoid mechanical cooling where possible, using passive cooling or alternative technology, will be critical to meet cooling needs for all sustainably.

Cooling is also a political challenge. Over the course of 2019 and 2020, in support of the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program, E3G conducted political economy analysis in countries with significant growth in cooling demand: Brazil, China, Indonesia, Mexico, and Thailand.

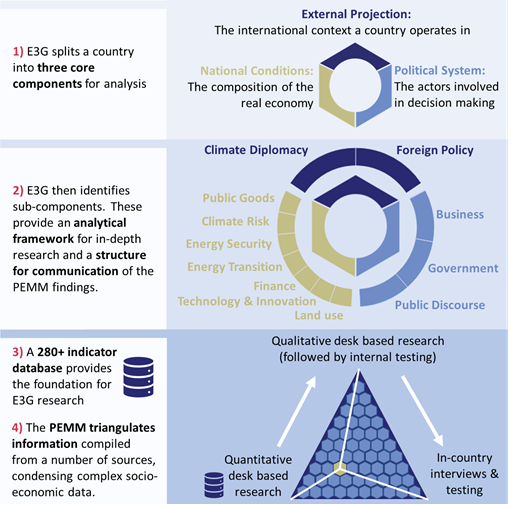

In each of these contexts, E3G investigated the conditions and trends that underpin core national interests and whether these conditions support or hinder the climate transition, delving particularly into cooling and related sectors. We mapped stakeholders to identify potential champions and blockers of a sustainable cooling transition. And we examined each country’s external projection – grounded in foreign policy and climate diplomacy – to understand how national conditions and the prevailing orientation of the political system come together to project a country’s interests internationally.

The content below delves into these three components – national conditions, political system, and external projection – that signal the broader politics of cooling and highlights the specific political economy of cooling in each country before presenting overarching routes to impact.

E3G Political Economy Mapping Methodology (PEMM)

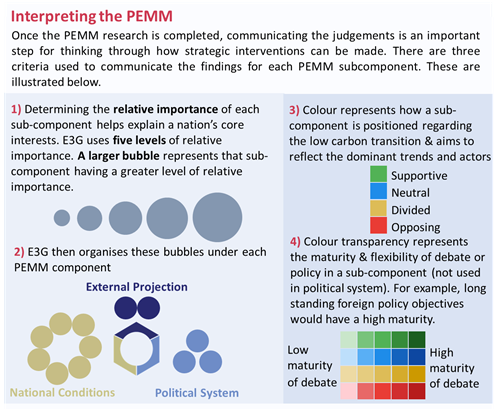

Political economy is the study of how a nation’s economic conditions interact with its political system and the resulting choices that society makes. The Political Economy Mapping Methodology (PEMM) analysis helps understand what constructs a country’s core national interests. This is used to assess threats and opportunities to countries presented by a low carbon transition. It is a tool to situate, test, and challenge how to think about strategic interventions.

This methodology provides an ability to process information in a transparent and consistent manner, creating comparability between countries and allowing judgements to be made. The framing for each subcomponent is determined by an E3G judgement, based upon information collected in both internal and external testing. This aims to reflect the dominant trends and actors within a subcomponent.

National Conditions: what underpins the sustainable cooling transition?

“Air conditioning was a most important invention for us, perhaps one of the signal inventions of history. It changed the nature of civilization by making development possible in the tropics.”

Lee Kuan Yew, former Prime Minister of Singapore

Across the five countries mapped, national conditions are split on a sustainable cooling transition, with climate risk and energy security potentially supportive, while energy transition and technology and innovation act largely as barriers, and finance, land use, and public goods are opportunity spaces.

While climate risk is increasingly a driver of climate action, for the cooling sector, climate risk has been less significant in supporting increased efficiency and sustainability. Heat waves, though becoming more frequent and widespread globally, are dubbed a ‘silent killer’, receiving less attention than other climate impacts such as intensifying droughts, storms, and wildfire seasons. However, this is changing with calls for heatwaves to be assigned names to raise the profile of the increasing risk excess heat poses and cities appointing Heat Officers to manage these risks. Climate risk – with a growing heat threat to human health and productivity – is the most supportive condition though has not yet been leveraged to its full potential to drive action on access to sustainable cooling.

Unmanaged, increasing cooling demand – both for thermal comfort and refrigeration – will increase the cost of energy transition and risks keeping fossil power online for longer than can be accommodated for limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Efficient cooling expedites and reduces the cost of the energy transition to net zero, particularly in those countries mapped below as cooling’s share of power demand increases. Even with years of evidence supporting the importance of energy efficiency to the energy transition, energy plans prioritize energy supply with less consideration of how cooling – as one example of demand side management – can reduce the cost and time to transition to net zero.

Cooling’s share of peak power demand is rising quickly. In China, by 2050, cooling is expected to contribute up to 50% and in Indonesia, the country that will drive more than half of air conditioning sales in Southeast Asia, total peak demand is expected to reach 260 GW up from 45 GW in 2020. An estimated 40% of this peak demand will come from space cooling. In Brazil, the rising number of cooling degree days drives space cooling use, with estimates that AC will make up more than 20% of demand and over 35% of power demand growth up to 2050. As governments and power companies try to meet the rising demand for peak electricity – including by increasing investment in coal and gas power generation – consumers will face rising electricity costs. Efficient cooling and passive, zero energy solutions can lower overall electricity demand and flatten the peaks, reducing the need for further investment at the cost of consumers and make energy more affordable for all. Without action to manage this pressure, cooling presents a challenge to the resilience and affordability of the energy system, made even more acute by heatwaves.

In 2018, the global market value of cooling equipment was larger than the market for solar PV panels and triple the value of wind turbines. This market, alongside renewables, is set to grow considerably. However, the nature of cooling means that this equipment is dispersed across numerous sectors and therefore has less prominence and geopolitical and trade attention than other technologies required for achieving decarbonization. Exports of air conditioners are dominated by Asia. China alone accounts for 35% of global exports and Thailand accounts for 12%. Exports of refrigeration equipment are balanced between Asia and Europe. This concentration of manufacturing means that a handful of countries and corporations can dictate the trajectory and adoption of energy efficient cooling equipment. Across most major cooling markets, the average efficiency of AC sold today is less than half of what is typically available – and one third that of the best available technology. However, as Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) in importing countries that have and can enforce them ratchet upwards, innovations in super-efficient appliances and ultra-low global warming potential refrigerants will drive export competitiveness. Innovation must also extend beyond the mechanical equipment used for cooling. Passive building design, which deploys non-mechanical infrastructure to cool a building, will be essential for reducing the need for power hungry AC units – and require innovation in governance, regulatory and business models to be deliverable at scale. While the technologies needed for the sustainable cooling transition exist, mobilizing technology and innovation is a particularly challenging barrier for the cooling transition given the critical roles of multiple technologies and the range and fragmentation of actors involved in their supply, distribution, and take-up.

Finance – both public and private – is a large opportunity space that needs to play an essential role in achieving net-zero cooling for all. Development finance institutions (DFIs) are key providers of catalytic finance, technical assistance, and as standard setters can help deliver at the scale and speed necessary for achieving sustainable cooling for all whilst contributing to their alignment commitments to the Paris Agreement and the SDGs. Private sector investors, with assets under management representing several trillions of dollars globally, have a critical role in delivering net zero cooling for all. Aside from the market opportunities created by sustainable cooling, for institutional investors, it would also contribute to their regulatory requirements to stress test and report on climate change risk. Despite these opportunities, the finance sector is only beginning to recognize the significance of cooling. Leveraging this recognition to build momentum through the green recovery wave and mainstream sustainable cooling within policies and portfolios is a rare opportunity to accelerate action on cooling and support that action with private and public finance.

Developing economies will be hit hard by increased exposure to heat including in terms of economic losses in heat–exposed sectors such as agriculture, fisheries, and construction. For example, in 2030, India is projected to lose up to USD 250 billion in labour hours due to heat exposure, putting at risk 4.5% of GDP. Across all regions, countries including Cambodia, Ghana, Panama, Qatar, and Spain, are expected to be significantly impacted by heat stress, both due to rising temperatures and the number of people employed in heat–exposed sectors. With the political importance often afforded to rural and coastal communities in the countries mapped below and growing focus on cold chain to build resilient and sustainable food systems, agriculture, fisheries, and land use considerations are an opportunity space. For example, to align with domestic policy in Brazil, cooling action can be framed as to the benefit of and to enhance the competitiveness of the Brazilian agribusiness industry while minimizing food loss and reducing pressure on land use change.

Cooling, in much of the world, is considered a luxury despite its critical role in economic development, productivity, and public wellbeing. While cooling is not yet widely considered a public good, health and air quality are core concerns of public interest and are also intimately connected with the cooling challenge. On health, vaccine delivery has taken centre-stage with effective vaccine rollout now a critical issue of public safety, government legitimacy and public support. Experts have identified significant barriers to a global vaccine roll out – citing existing major challenges, particularly in low-income countries – including insufficient cold chain capacity, outdated and inefficient cold chain equipment, inadequate maintenance, lack of investment in skills and training, limited energy access, and a lack of financing and sustainable business models. On air quality, pollution is a core threat to the legitimacy and effectiveness of city governments in providing safe environments for their residents. Reduced energy demand for cooling will reduce the need for carbon and air pollutant intensive energy generation. In addition, in cities in Brazil and China with comparatively low space cooling needs, AC is considered necessary because of poor air quality – often precluding the ability to cool spaces naturally. This was also the case in the US during the 2020 wildfire season with AC sales jumping as people sought out air purification solutions.

As our food systems and living and working environments are challenged by Covid-19 and climate change, these too are becoming core public concerns. Cooling – both cold chains and comfort cooling – are critical to building and maintaining resilient food systems and creating safe environments. As governments are pressed to provide a safe climate for people, cooling can deliver both in terms of raising the bar on mitigation of and laying the groundwork for adaption to climate change. With an impending rise in temperatures and a lack of access to cooling, developing countries – especially those in the tropics – will be hit hardest in terms of health, productivity, and development goals.

The visualization below provides a broad overview of the net-zero and sustainable cooling challenges and opportunities within the national conditions of each of the five countries mapped as part of the political economy analysis conducted by E3G under the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program.

National Conditions overview – hover over a coloured circle to find out more for that component. These visualizations and tool tip functions are best viewed on a desktop.

Political System: who supports a sustainable cooling transition?

”The civil rights revolution and air-conditioning are the two biggest factors that have changed demography and a lot of our politics in the last 30 years.”

Richard P. Nathan, former director of the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Across the five countries mapped, the political system is split on a sustainable cooling transition with government largely leading the way and industry divided while public discourse – though with less space for impact – is supportive.

National cooling action plans, first published by China, India, Rwanda, and others, have gained prominence as a tool to organize government policy and resources – Minimum Energy Performance Standards, labels, building codes, innovation funding – around the cooling challenge. However, even in China and Thailand – the two largest producers of cooling equipment globally – cooling is not viewed with proportionate strategic importance, despite the growing political recognition of mitigating and adapting to climate change and risks including heat. Within energy ministries, sustainable cooling as a demand side management tool is often side-lined and not integrated into long-term energy planning. To gain traction outside of National Ozone Units and energy efficiency agencies, cooling and its benefits must be framed as strategic to political priorities – competitiveness, energy security, food security, job creation, productivity, foreign direct investment – as well as a concrete and vital element of climate mitigation and adaptation. This framing – taken forward by tools such as national or city level cooling action plans – will enable more cohesive and effective action on cooling and can overcome tensions between supporting innovators and protecting laggards in the private sector.

Cooling manufacturers have made significant contributions to cooling transition however, in some contexts, lag the ambition of government and civil society. This reluctance to lead on the cooling transition is rooted in the lack of strategic relevance cooling carries within the technology and innovation sphere. However, this dynamic could be shifted if sustainable cooling is positioned to complement the bottom line of business, the development priorities of governments, and a push for export and trade opportunities. Expanding the view of cooling beyond appliances and minimum energy performance standards is crucial to consider the wider ecosystem of private sector actors that impact cooling, for example, architects, the construction industry, and building developers. For the race to zero in the cooling sector to be realized, passive solutions and businesses engaged in passive design will need to be brought to the table.

Public discourse and consumer choice are largely positive on climate action but often do not carry as much weight as government and business in national discourse with shrinking space for civil society. Sustainable cooling as a necessity for health, productivity, and economic stability has not yet emerged as a key point in climate and net-zero public debate. Civil society actors could be more fully activated on the sustainable cooling transition by aligning it with their specific priorities and the role of cooling in achieving them. While cooling is largely seen as an appliance and consumer goods issue, reframing cooling as a public service – delivered through urban environments, buildings, mobility, and rural infrastructure – and as a strategic food and health sector component can elevate its contribution to core public good discussions. In addition, ‘cooling as individual appliance’ can be repositioned as ‘cooling as infrastructure’: given the lifespan of most cooling equipment exceeds 10 years, individual investments in millions of low-efficiency appliances now will on aggregate amount to a stranded infrastructure asset that will need to be replaced, incurring avoidable costs and complex distributional impacts.

The visualization below provides a broad overview of the net-zero and sustainable cooling challenges and opportunities within the political system of each of the five countries mapped as part of the political economy analysis conducted by E3G under the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program.

Political System overview – hover over a coloured circle to find out more for that component. These visualizations and tool tip functions are best viewed on a desktop.

External Projection: how can cooling support foreign policy and climate diplomacy priorities?

“When you had this money coming in from the rest of the world for high-end buildings, it often came with an American or European designer or consultancy attached… And so it comes as a package with AC. They thought that meant progress.”

Ashok Lall, architect and sustainability expert

Across the five countries mapped, external projection is largely supportive or not yet capturing the strategic importance of the sustainable cooling transition. However, the trend is shifting quickly.

Though an opportunity space and important piece of the climate transition, cooling – as both a climate and economic issue – has not yet been integrated as a foreign policy priority. Given cooling’s significance for trade – in terms of appliances, components and with cold chain an enabler of food and pharmaceutical exports and imports – there is an opportunity to position cooling as strategically significant to the ‘big’ trade issues, for example, competitiveness of manufacturing, productivity, food security and export dominance. Global AC exports (by value) in 2018 were concentrated in Asia, a region that has also seen the biggest rise in exports since 2008. China alone accounts for 35% of global AC exports and Thailand accounts for 12%. While AC exports volumes are largest in Asia, AC imports are concentrated in Europe, Asia, and North America with the latter two seeing a large increase in imports since 2008. Tariffs also impact trade and high tariffs could inhibit the uptake of more efficient AC because of higher upfront costs, even if life–cycle costs are lower. Wider trade dynamics have significant impacts for the evolution of the cooling industry globally. For example, the production of semiconductors – computer chips – which are a core component of cooling appliances, has been a key issue in trade tensions between China and the USA as technology giants. China is prioritizing self-reliance, ramping up production to localize supply with Gree Electric Appliances and Midea Group stepping up R&D on semi-conductors.

While more than 115 countries have ratified the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol and over 45 countries have included cooling in their enhanced Nationally Determined Contribution, many of the largest players – in terms of cooling growth and manufacturing – have been noticeably absent. Of the five countries mapped, only Mexico has ratified the Kigali Amendment [as of May 2021]. Signalling a recent shift in the significance of cooling in setting and meeting ambitious climate mitigation targets and adaptation goals, both the USA and China – two of the largest producers and users of cooling equipment globally – have committed to implementing the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol. Bridging climate diplomacy and foreign policy, ensuring convergence towards high energy efficiency standards in free trade agreements can be complementary to domestic and international efforts on Minimum Energy Performance Standards. However, joining up trade negotiations with forums that establish energy efficiency standards is challenging and requires international collaboration. Initiatives like the BRI Green Cooling Initiative, CLASP and Efficiency For All can help bridge this gap, by supporting the formulation of markets for energy efficient appliances. Beyond the necessary improvements in mechanical cooling, harnessing foreign policy and diplomatic forces to drive the diffusion of passive solutions is more challenging given the complexity of building standards and urban planning mechanisms. Philanthropy as well as bilateral and multilateral development support have a key role to play in supporting the adoption of passive cooling solutions at scale to capture climate, health, social, and economic benefits. The UN Environment Programme coordinated Cool Coalition – through topical working groups – offers a multilateral, cross-sectoral approaches to supporting passive cooling solutions as a first principle, encouraging whole of system approaches to sustainable cooling.

The visualization below provides a broad overview of the net-zero and sustainable cooling challenges and opportunities within the external projection of each of the five countries mapped as part of the political economy analysis conducted by E3G under the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program.

External Projection overview – hover over a coloured circle to find out more for that component. These visualizations and tool tip functions are best viewed on a desktop.

Routes to Impact: what are the multiple pathways to net zero cooling?

Cooling, recognized as a strategic priority by national and sub-national governments, businesses, public and private financial institutions, and communities for climate action and sustainable development, will be reshaped in a net-zero world to meet all cooling needs.

A world with net-zero cooling avoids mechanical cooling, wherever possible, massively reducing energy demand for cooling and shifts the load to renewable energy and district cooling. Mechanical cooling, where necessary, must be super-efficient, building on the success of technological innovation and clear minimum energy performance regulations, and minimizes or eliminates the use of refrigerants with global warming potential. Sustainable cooling is necessary to protect the most vulnerable from extreme heat and ensure cooling is available and affordable for all who need it.

As highlighted by the COP26 Champions Team in the Net Zero Cooling Pathways, there are a variety of pathways to ensure sustainable cooling for all. Successful pathways will require different technologies, actors, financing, and more depending on the cooling needs of people, economic activities of a region, prevailing climate and likely climate impacts, and a multitude of local, place-based considerations.

To accelerate and achieve net zero cooling globally at the scale and speed needed for a climate-safe world, three key drivers, which correlate with broader shifts in economic and social development, should be prioritized.

- Rethinking consumption patterns: For cooling this means investing in, planning for, and integrating passive cooling and design as a first principle. This approach avoids the need for mechanical cooling, where possible, expands the reach and creativity of cooling solutions, and protects the most vulnerable. We are already seeing examples of countries and regions rethinking consumptions patterns, for example, in China with Ecological Civilization and in the EU with circular economy action plans which can extend to and be exemplified by a sustainable cooling transition.

- Competition within global cooperation: Recent regulatory successes in Brazil and China have raised the floor for energy efficiency of cooling appliances in major manufacturing countries, but achieving net-zero cooling at scale and speed will require lifting the ceiling. Industry must race to the top to get to net zero cooling as quickly as possible, building for example on the innovations and successes of the Global Cooling Prize finalists from China, India, Japan, UK, and USA. First movers will benefit from new, more efficient ways of delivering cooling, raising the bar for all cooling manufacturers, and driving down costs for more efficient designs benefiting end-users.

- Riding the recovery wave to systemic change: COVID-19 has presented the world an unprecedented challenge and opportunity. The pandemic has drawn attention to stark inequalities, shifted work and travel patterns, and revealed vulnerabilities in our food and health systems. The investments in recovery being made now by governments and public and private financial institutions will define a critical decade to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change. There is a significant opportunity for sustainable cooling for all to be mainstreamed within these investments as a standard – crucial to safe working conditions, resilient food systems, and effective health care – to contribute to a green and resilient recovery that sets up the long-term structural and systemic change needed for a climate-safe world. Taking advantage of this recovery wave, the cooling sector can accelerate action under the Kigali Amendment taking advantage of large-scale recovery investments and packages leveraging the contribution of cooling to achieve the sustainable development and Paris agendas.

Cool Resources Library

E3G, supported by the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program, and in collaboration with other actors in the cooling community have produced the following knowledge resources.

- For shorter reads by our team, see these pieces on cooling in the health sector, MDB agendas, energy security, and global trade or our recent newsletters from May 2020 and December 2020.

- For longer pieces, see our recent reports from E3G on cooling and the COVID-19 recovery and the role of Development Financial Institutions in sustainable cooling.

- For engagement with other actors in the cooling and climate communities, watch recent webinars on integrating sustainable cooling in recovery policies, financing cooling in a warming world, cooling and recovery in the lead up to COP26.

- To see what our team is up to now, go to our team page.

About E3G

E3G is an independent climate change think tank accelerating the transition to a climate-safe world. E3G builds cross-sectoral coalitions to achieve carefully defined outcomes chosen for their capacity to leverage change. E3G works closely with like-minded partners in Government, politics, business, civil society, science, the media, public interest foundations and elsewhere. More information is available at www.e3g.org

Copyright – This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike 2.0 License. © E3G 2021