The Covid-19 pandemic is hitting coal power generation hard around the world. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that coal demand will drop by 8% across the year, putting coal on an accelerated downward path.

Will governments heed the call of UN Secretary General Guterres to exclude coal from their recovery plans? Or will policy makers provide further subsidies in a perverse attempt to help coal bounce back?

Our new global status of coal power review, published here, provides a comparative analysis of country performance across a range of coal transition metrics. It provides a baseline of global and country-level coal power generation trends prior to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. As the economic recovery moves forward, we will continue to track these trends and identify where progress is being made and where further efforts are required.

Coal phase-out continues apace in the EU28 and USA

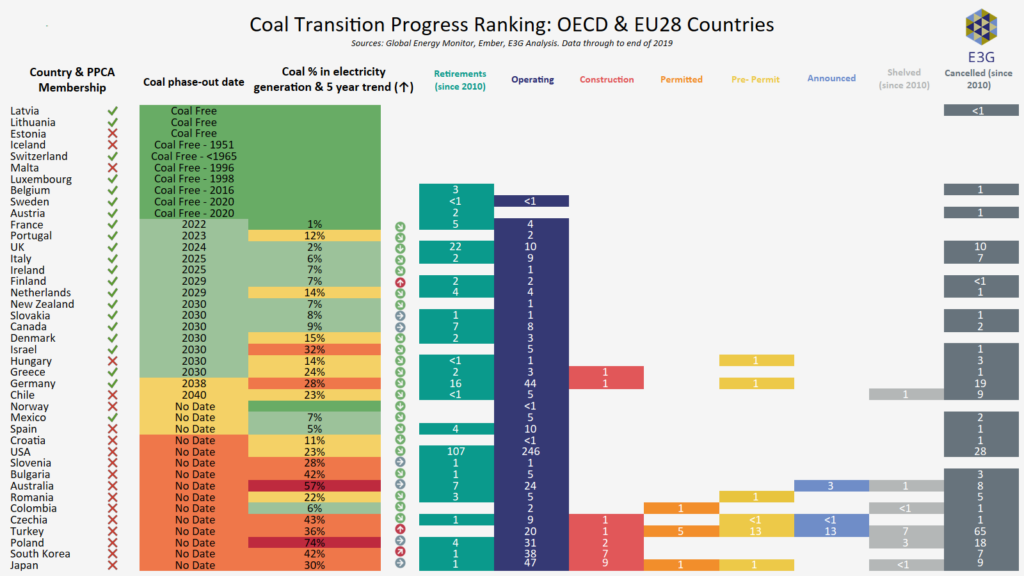

Our analysis for this review includes the first ever ranking of OECD & EU28 progress on coal transition, finding that 71% of OECD and EU28 member countries are already pursuing coal phase-out, with 58% on track to be coal free by 2030.

We compared the level of scheduled retirements of coal power plants against the total operating capacity in place as of January 2020, finding that 35% of OECD & EU28 coal capacity is scheduled for closure before 2030, plus a further 6% currently has a post-2030 closure date.

But the exit from coal in OECD & EU28 countries has already been gathering pace over the past decade, so a more accurate approach comes from including power plant retirements since 2010. Using this starting point, we find that 52% of OECD & EU28 coal capacity has either closed already or is scheduled to close by 2030.

These calculations of progress by 2030 incorporate Japan’s recent announcement that it intends to close over 20GW of older power plants by that date. But Japan is still planning to build new coal plants both at home and abroad: it sits bottom of our ranking of OECD & EU28 countries as a result.

Similarly, while the OECD & EU28 countries are home to 39GW of proposed new coal projects, 81% of these are in Turkey alone. The Covid19 economic crisis and recovery presents an opening for policy makers to avoid locking in expensive stranded assets if they divert investment from dirty coal to clean energy alternatives.

Figure 1: Coal transition ranking progress in OECD & EU28

Our analysis of the OECD & EU28 also highlights another trend – the unofficial race between the EU and USA over who can achieve coal exit quickest. In spite of pro-coal rhetoric from the White House, US coal generation has halved since its 2007 peak, while across the Atlantic the EU is down to just 50GW of operating coal capacity not yet having a retirement date. Half of Spain’s coal power capacity closed in June and the UK witnessed over two months of coal-free electricity generation. Germany has made progress through the adoption of its coal phase out law, but its 2038 timeframe for coal phase out will need to accelerate further to respond to market dynamics and climate goals.

More countries eschewing coal than pursuing coal

When looking at the global data through to the end of 2019, we find that 56 countries already had no new coal projects under development prior to the Covid19 pandemic, up from 52 in 2019. 14 non-OECD countries with operating coal capacity could immediately commit to no new coal and consider phase-out pathways, as they have no new projects under development.

Of the 52 countries that still had a pipeline of new coal projects at the end of 2019, our analysis finds that at least half of these could readily commit to no new coal. We anticipate that these numbers will increase as a result of post-Covid19 economic decision-making. Among the non-OECD, 20 countries were already well-positioned to commit to no new coal prior to the crisis:

- 11 of these are currently coal-free countries that can avoid the economic risks of coal by leapfrogging straight to clean energy (as Egypt has done by stepping away from massive Hamrawein project in early 2020).

- 9 have existing coal projects but nothing currently under construction – moving away from their pipelines would put them on the pathway to a coal free future and avoid stranded assets.

The risk of new coal plant construction was concentrated in just 15 non-OECD countries in January 2020. The Covid19-induced economic recession challenges the case for new coal power generation and increases the importance of policy makers pursuing sustainable, resilient, and clean energy investments.

There remains a risk that policy short-termism around Covid19 recovery drives the rebound of coal generation and construction, and locks in uneconomic new plants. Recent analysis of China shows that provincial economic recovery goals are driving investment in uneconomic new coal projects. The pipeline of new projects in China has further increased during the first half of 2020, with 17 GW of new projects permitted through June, more than all of 2018 and 2019 combined.

China subsequently continues to be home to over half the world’s existing coal power capacity and projects under construction. While central government has issued guidance seeking to restrict coal construction, provincial leaders are actively encouraging new coal plants to be built to stimulate economic activity, despite overcapacity and high and increasing risk of stranded assets.

Methodology, data sources, future updates

Our analysis brings together datasets from Global Energy Monitor and Ember, supplemented with E3G analysis of governments’ political commitments and policy developments. Aggregating this data to the country level allows us to build a comparative picture of progress among economic peers and regional groupings.

This first edition of our global status of coal power review is a means of us sharing our initial analysis to provide a baseline of trends prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. The accompanying slides provide some ‘spotlight’ insights that highlight and analyse new and emerging trends from the first half of 2020 that will feature in the next releases of the datasets.

We aim to update our analysis as new data becomes available, either on an annual or biannual basis. We are also working with partners to develop additional tools and data visualisations that can be used more widely.