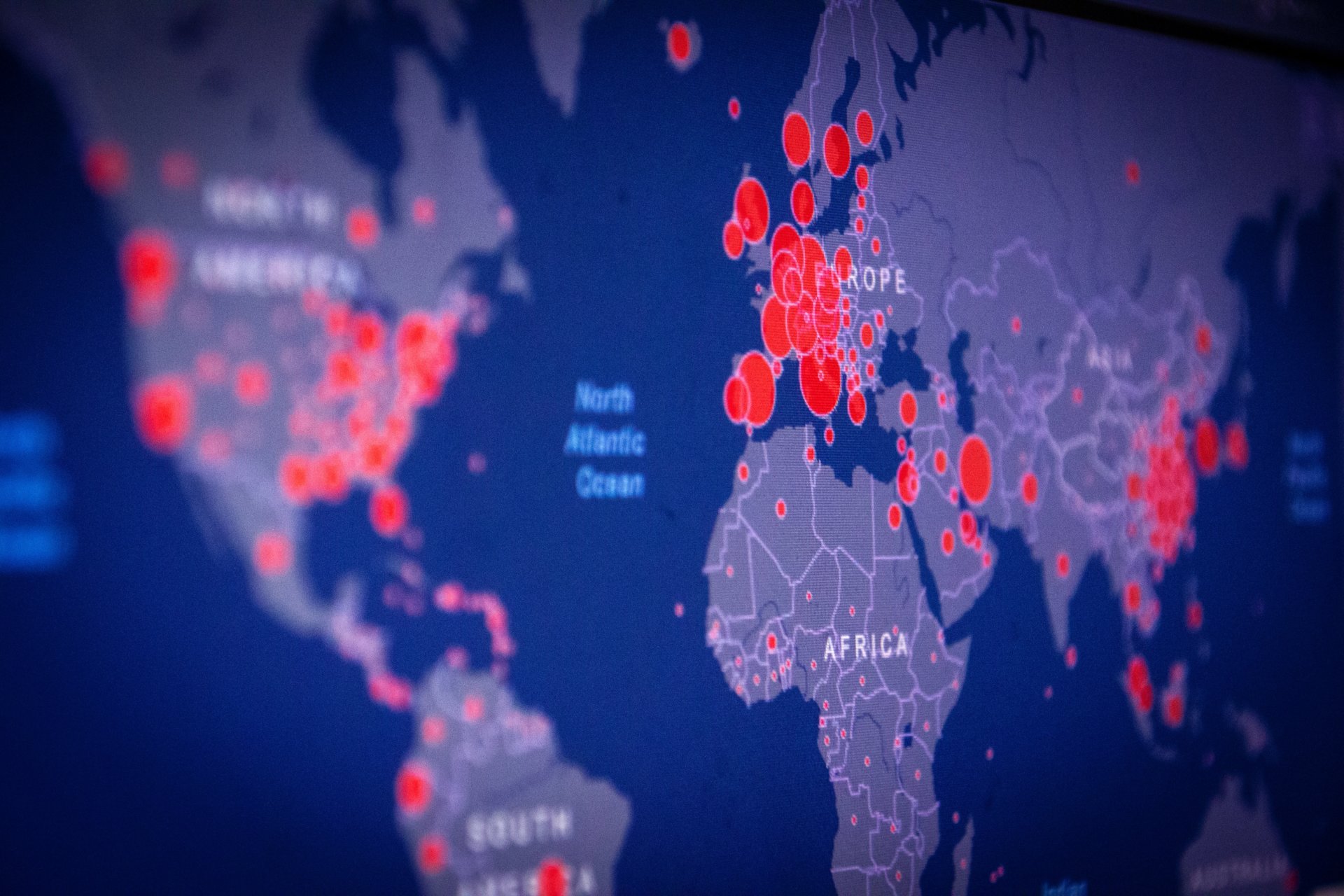

COVID-19 has disrupted the geopolitical landscape creating new challenges, barriers and opportunities for multilateral cooperation on global issues.

E3G is monitoring geopolitical developments in this new landscape to track how the space for cooperation is evolving and its implications for global climate action. This memo provides a snapshot of our latest conclusions from this monitoring.

Initial conclusions

E3G’s tracking of geopolitical developments since April 2020 has shown:

- The COVID-19 pandemic is a global risk that requires global cooperation to solve, and its challenges cannot be addressed in isolation. To date, cooperation has been inadequate and fractured. The overall consensus among experts is that global cooperation has failed to tackle the COVID-19 crisis with only 32.6% of 900 international relations scholars describing the global cooperation as very or somewhat effective.

- However, there have been some good examples of where cooperation has prospered. This includes extensive financial support and international aid raised to tackle the immediate health crisis, as well as regional, sub-national and private sector cooperation. The final section of this paper provides further detail of the examples of cooperation seen during the COVID-19 crisis.

- In particular, climate change and calls for a green recovery have so far remained an issue where countries have been willing to cooperate, in multilateral fora such as the Placencia Ambition Forum, the Petersberg Climate Dialogue, the UNFCCC June Momentum and the IEA Clean Energy Transitions Summit. This raises hope for a pathway to successful outcomes at COP26. Climate change cooperation can serve as the foundations for building broader global cooperation in response to COVID-19, bolstering the multilateral system and rebuilding faith in the need for rules-based systems. However, if it is to succeed it will require efforts to ensure that climate action is complementary to wider, urgent COVID-19 issues requiring immediate cooperation, including global public health, food security and debt relief. Building these links will entail shifting dialogues from the realm of environment and climate change ministers, towards the attention of leaders and finance ministers, in order to bring top-down political drive to climate action to ensure its position as a top-tier geopolitical issue of relevance to the current crisis.

- The pandemic has accelerated pre-existing geopolitical trends, particularly the decline in the US engagement globally and a spike in its rivalry with China. China continues to seek to fill the political vacuum in the multilateral system left by a more isolationist USA. This has been powerfully demonstrated recently at the UN Human Rights Council, where 53 countries supported China, against 27 countries that called for action on issues including Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Tibet. Escalated US-China tensions risk rendering multilateral fora – including the UNFCCC and COP 26 – key battlegrounds for these global powers.

- Geopolitics has become highly volatile. The crisis is not limited to the health and economic impacts of COVID-19. Heightened tensions on the India-China border, rising maritime activity in the Asia-Pacific, global outcry at China’s decision to impose new national security legislation in Hong Kong, disinformation campaigns spreading fake news – all these examples, and more, are symptoms of a de-stabilised geopolitical system. Even the Black Lives Matter protests in the US (which have spread globally) are arguably reflective of this more volatile political climate.

- Many high-profile efforts from international institutions are not concrete actions, but rather statements, calls to action or pleas. Action has been limited for structural reasons – the WHO, for example, faces problems of a limited mandate, funding, and jurisdiction; as well as political ones – for example, the UN Security Council, the G20 and the G7 have been unable to drive extensive coordinated action. This has led to disappointing outcomes. For example, the loan financing and suspension of debt payments measures by the G20, World Bank and IMF are seen as insufficient as they do not cover all the financing requirements of the Global South.

- In light of the many challenges faced by multilateralism, some countries are looking to alternative alliances – be it the UK’s D10 proposal, or Australia’s coalition of ‘First Movers’ – in which ‘minilateralism’ (convenings of a limited number of countries cooperating on an issue-by-issue basis) is creating opportunities where multilateralism has been unable to. It is too early to tell whether these minilateral alliances will serve to either exacerbate or mend tensions in multilateralism more broadly. Minilateralism may benefit policy implementation in the short-term, but risks undermining a more global rules-based approach and raises further questions about who gets a seat at the world’s diplomatic tables.

- Traditional venues for diplomacy within the rules-based world order are being disrupted as a result of the political forces, both international and domestic, unleashed by COVID-19. Multilateral institutions such as the WHO have become highly politicised – as demonstrated by the US decision to withdraw from the body and the highly fraught World Health Assembly at which powers battled over the decision to commission an investigation into the pandemic. The G7 has also become a contested forum with an uncertain future, following the USA’s proposal to include Russia and expand membership to Australia, South Korea and India.

- The poorest and most vulnerable countries continue to express concerns that developed nations are failing them during the pandemic. Efforts to bridge these divides will be necessary to set the conditions for ambitious outcomes on climate action. Pledges must now turn to action. These actors are particularly affected by a weakened multilateral system, becoming more exposed to bilateral political tensions and losing the global platforms in which they can make the voice heard.

- Climate is not the only issue that will require global cooperation over the next months ahead. This includes not only cooperation to strengthen health systems and tackle the pandemic, but also cooperation to handle related consequences of COVID-19 including debt relief, food security, humanitarian development, global security, macroeconomic stability and peacebuilding.

Read the full briefing, Global Cooperation during COVID-19, here.