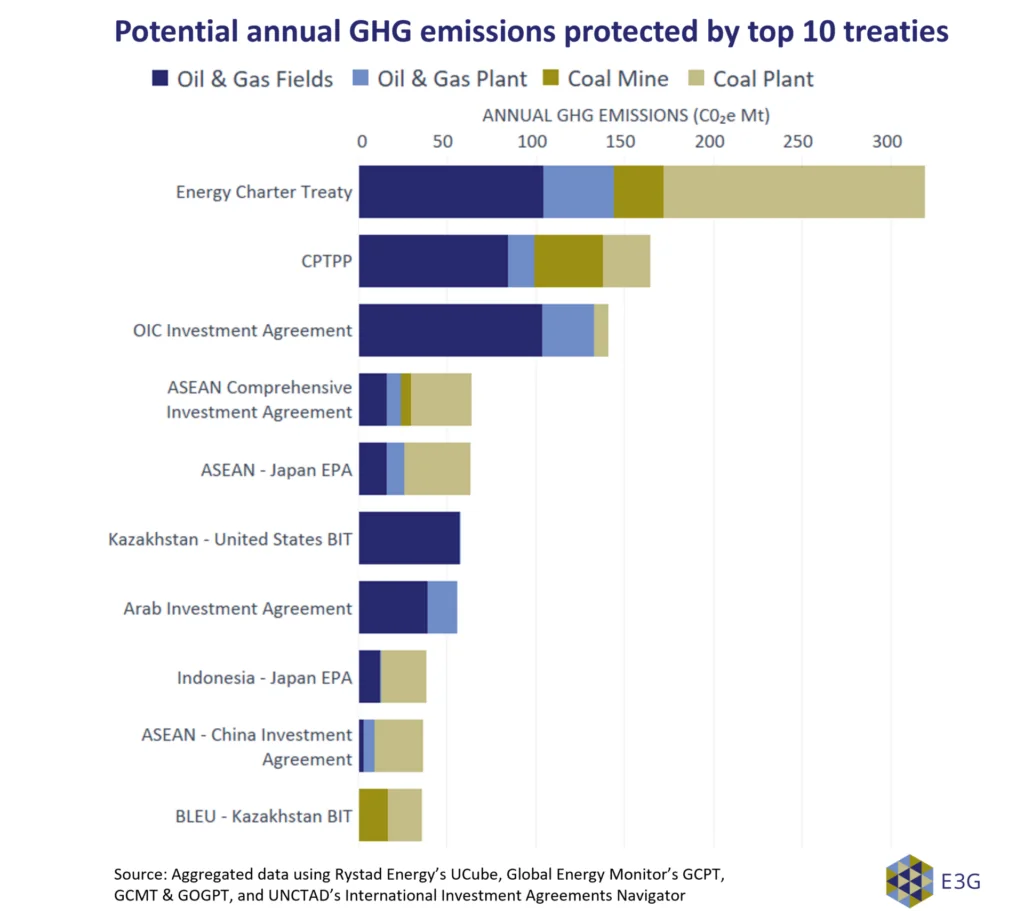

Our ranking reveals that the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) remains the most dangerous investment treaty to the energy transition by protecting over 300 megatonnes (Mt) of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (CO2e). Recognising this threat, the EU, the UK and ten EU countries have already withdrawn or decided to leave the treaty since 2022. However, the remaining contracting parties to the ECT voted to approve the reformed treaty text yesterday, despite it still not being compatible with achieving climate goals due to its continued protection of fossil fuels.

Investment treaties with investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) provisions, such as the ECT, could jeopardise the energy transition by allowing foreign investors to bring claims against host governments in international arbitration tribunals. Our recent report found that global fossil fuel assets, protected by ISDS in nearly 2,500 treaties, emit up to a potential 2 gigatonnes (Gt) of GHG emissions annually.

The ECT isn’t the only investment treaty that threatens the energy transition. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which the UK will formally join by the 15th December 2024, protects the second largest amount of GHG emissions.

As we enter 2025, a critical year for climate ambition, investment treaty reform must be top of the climate agenda.

Key acronyms

- ASEAN: Association of Southeast Asian Nations

- BIT: Bilateral Investment Treaty

- BLEU: Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union

- CPTPP: Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership

- EPA: Economic Partnership Agreements

- OIC: Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

The Energy Charter Treaty protects the most GHG emissions

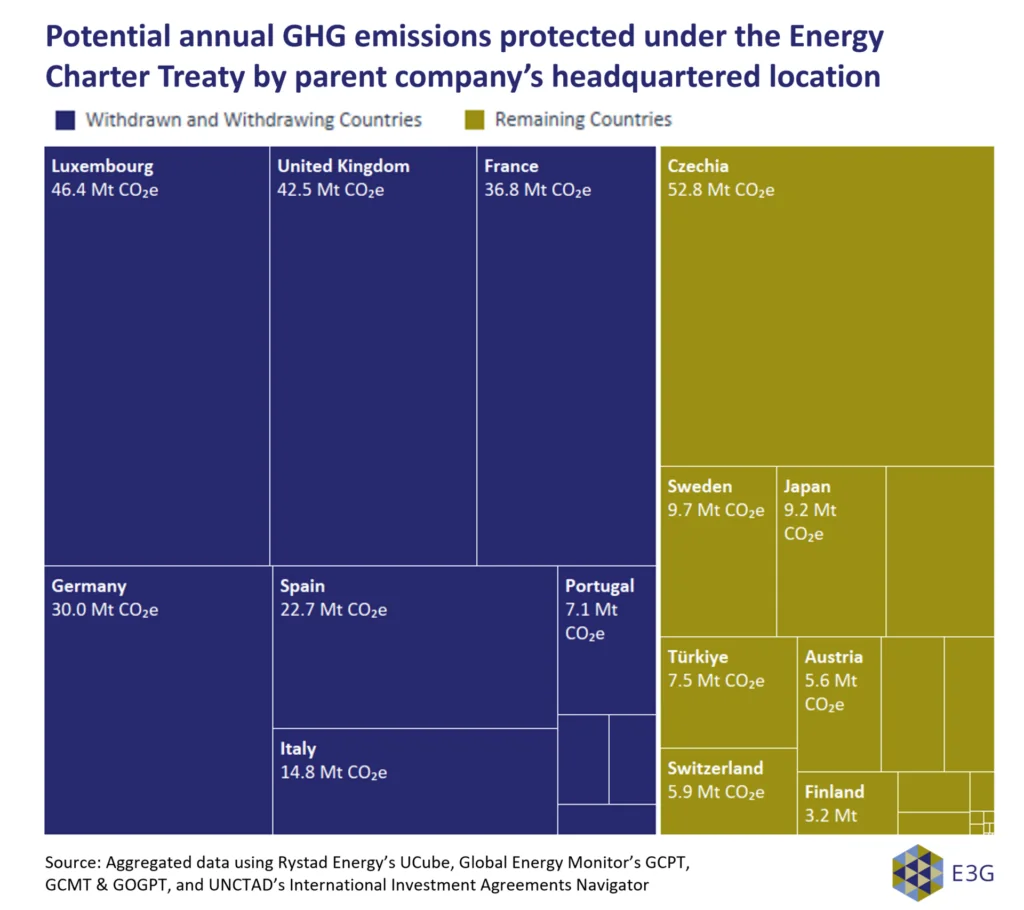

The Energy Charter Treaty protects the most GHG emissions from fossil fuel assets in comparison to every other treaty. This equates to a potential 319.7 Mt CO2e, three quarters of which is from fossil fuel assets owned by parent companies headquartered in EU member states.

The ECT’s sunset clause means that fossil fuel investors will still be able to make claims against countries which have withdrawn, continuing to protect investment decisions prior to the date of withdrawal for twenty years.

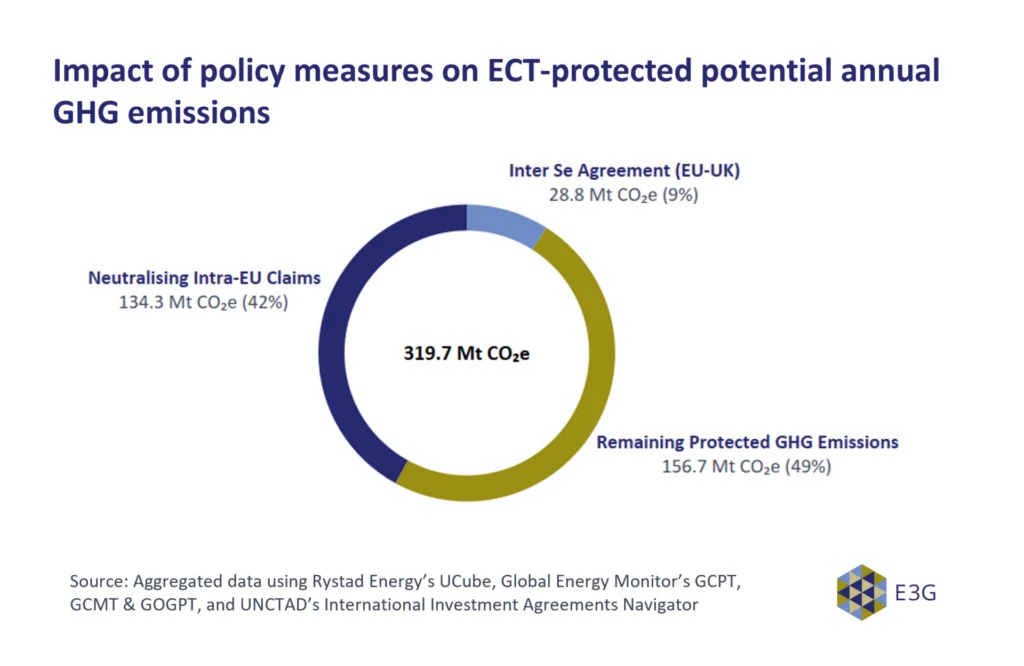

There are ways to mitigate the threat posed by the ECT. The EU has taken an important step to ensure that the ECT arbitration provisions cannot apply in intra-EU relations. This measure would potentially remove 42% of GHG emissions protected by the ECT.

An additional 9% of GHG emissions protected by the ECT could be removed if the UK and EU member states that have left or decided to leave the ECT since 2016 negotiated a separate agreement to neutralise the sunset clause.

The other ECT signatories also need to leave the treaty to tackle the remaining protected GHG emissions (49%).

The other climate-damaging treaties

Our ranking also reveals which other treaties are most responsible for protecting emissions via ISDS. The CPTPP protects the second most GHG emissions via ISDS: a potential 164.9 Mt CO2e from fossil fuels assets annually.

The UK’s formal accession to the CPTPP will take place by 15 December 2024. The UK already has investment treaties with ISDS with most CPTPP signatories, but its accession to the CPTPP will create an ISDS relationship with Brunei and potentially Canada, if ratified.

Australia, New Zealand and the UK have signed ‘side instruments’ with some CPTPP members to remove or restrict access to ISDS. While this can be an easy way of preventing new ISDS relationships, CPTPP members need to collectively address its ISDS protection for fossil fuel assets.

Treaties protecting large amounts of emissions are mostly multilateral or involve more than two countries. However, two bilateral agreements also appear on the top 10 list: Kazakhstan-US BIT and Indonesia-Japan EPA. The global coverage of fossil fuels protected by these eight other treaties highlights the need for global coordinated reform.

2025: The year for investment treaty reform?

It is essential for countries to join forces to reform investment treaties with ISDS in a coordinated way. Integrating the investment treaty reform into wider climate discussions at G7/G20 and UNFCCC processes can create political momentum to make progress in technical discussions at the OECD, UNCITRAL and UNCTAD.

2025 provides opportunities for change. Both South Africa and Brazil, next year’s respective presidencies of the G20 and COP30, have taken a progressive approach to ISDS. ISDS and its fossil fuel protection has already been identified as a potential area for exploration in 2025 in the UNFCCC discussions on aligning finance flows.

Our ranking is a rallying call. The countries signed up to these treaties need to capitalise on these presidencies in 2025 and align investment treaties with climate goals.

The figures have been drawn from the database behind our report. The full methodology for how we mapped fossil fuel assets, and their associated greenhouse gas emissions, protected by ISDS can be found in Annex A of our report.

We used the following databases for our analysis:

- Rystad Energy: UCube

- Global Energy Monitor: Global Coal Plant Tracker (GCPT), Global Coal Mine Tracker (GCMT), Global Oil and Gas Plant Tracker (GOGPT)

- UN Trade & Development: International Investment Agreement Navigator

The analysis in this blog aggregated asset-level and unit-level data to the level of individual treaties. Given that more than one treaty can protect a fossil fuel asset and investors can choose which treaty to invoke in an ISDS case, this ranking includes duplicate results for fossil fuel assets that are protected by more than one investment treaty. As such, the figure should not be aggregated to a total figure and are only in relation to the individual treaty specified.