Investments in the infrastructure and services needed to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C are estimated at $1.3 trillion per year by 2030. The background where this investment needs to take place is notably challenging. Since late 2019, soaring interest rates coupled with weak growth prospects triggered a global surge in indebtedness; COVID-19 halted the era of low inflation and historically rock-bottom interest rates. However, climate change gallops on, and as such it will impact countries’ financing needs, and their abilities to service debt. At this critical juncture, strong political leadership is needed around new rules and mechanisms to free up investment capacities in developing and emerging economies.

While debt-to-GDP ratios increased across most countries and remained higher in advanced economies, the burden of debt servicing unfolded in disparate ways. From August 2019 to August 2023, G7 nations witnessed a gradual increase in their average long-term interest rate from 0.6% to 3%, while developing and emerging economies were more severely hit. For example, Colombia experienced a surge from 6% to 11%, and Kenya’s rate rose to 16% from the already high 11% within the same time frame.

Such elevated interest rates left numerous developing nations vulnerable to substantial debt risks. Between late 2019 and late 2022, around 49 developing nations faced downgrades from prominent credit rating agencies. By December 2022, eight of these countries had defaulted, with an additional four undergoing debt distress.

Given the prevailing risks, there has been a substantial effort focused on immediate debt relief, and the IMF has continued to argue for fiscal consolidation as a key priority. However, the climate imperative compels developing and emerging countries to increase their borrowing in the near future. High interest rates, and high existing debt levels, will directly limit borrowing and investment capacity, including climate-focused investments. This impediment increases the risk of a vicious cycle of underdevelopment along with delayed climate preparedness and transition.

Emerging coalitions call for an ambitious agenda on the future of debt

This hasn’t passed unnoticed. Numerous experts sounded the alarm early on that a debt crisis was brewing, while the IMF called to reform the debt architecture as early as October 2020. The G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative, along with the Common Framework, was one attempt to provide an umbrella for action on debt during the pandemic, but its impact has been limited.

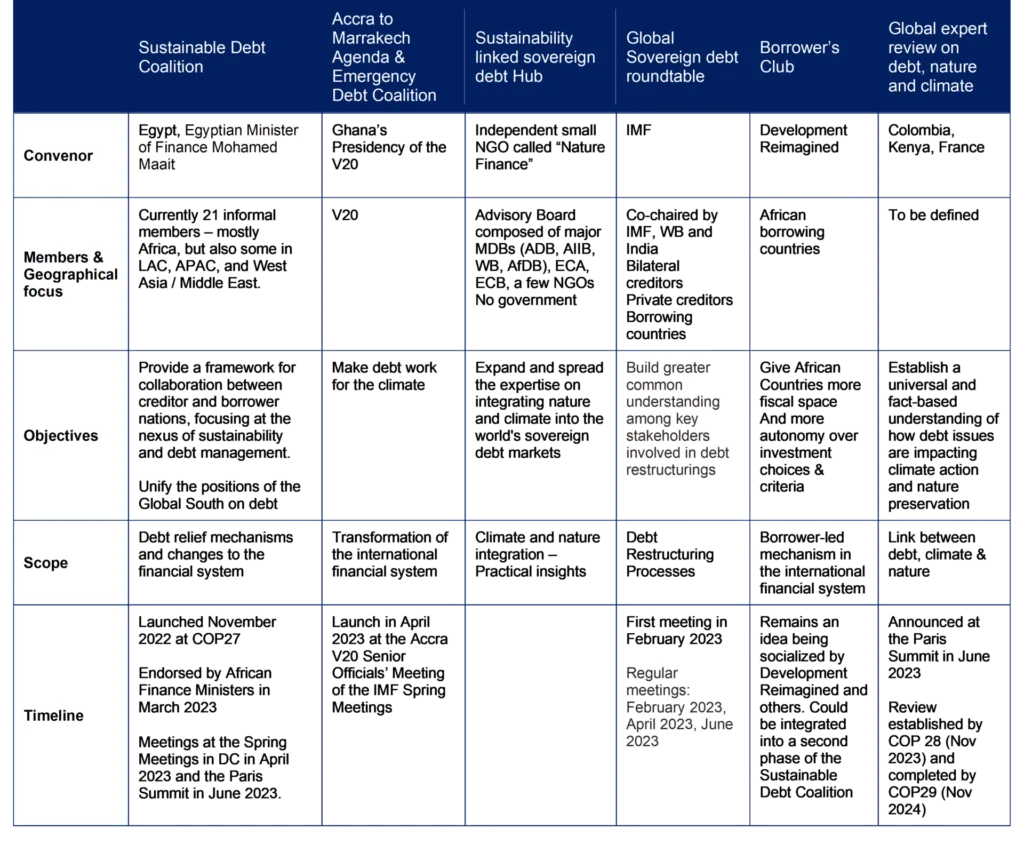

More recently, we have seen the emergence of different initiatives, including the Sustainable Debt Coalition and the V20 Accra to Marrakech Agenda. Both stressed the need to look not only into debt relief but also into structural changes to the international lending framework, allowing for broader fiscal space. Supporting those claims, research has found that countries’ creditworthiness benefits more from a significant investment push (fostering economic growth) than from fiscal consolidation (reducing indebtedness). Proposals being discussed within those coalitions include systematic Climate-Resilient Debt Clauses, rechannelling unused SDRs, scaling up grant-based financing for global public goods, and reforming the IMF Debt Sustainability Assessments.

Below is a non-exhaustive list of some of the initiatives that have emerged over the last few years. These show the strong impetus for developing new mechanisms to allow for additional finance to flow towards developing and emerging economies.

Political leadership is key for delivery

Most of the initiatives are championed by developing economies and although promising, have yet to find a political mechanism for delivery.

The Expert Review on Debt, Nature and Climate – announced by Colombia, Kenya, and France in June 2023 – could play a key role in building the necessary momentum for delivery. The “Review” builds on the Paris political momentum and will leverage the upcoming series of summits, including IMF/World Bank Annual Meetings and COP28. It stands out for its combination of a research-based focus with strong political ownership from a range of developed to developing countries. Debt, and the macroeconomy, are notoriously prone to being a technical issue, subject to rules and implicit regulations, while simultaneously very political – in that key economic decisions are a matter for governments, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 Crisis.

There will remain massive challenges to transform this initiative into a platform with both sustained political interest and capacity to set up new rules and mechanisms for a systemic response to the debt and climate crisis.