In November 2017, a meeting room in Bonn witnessed a watershed moment. In the margins of COP23, Canada and the UK launched the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA).

Its creation provided an injection of energy to global climate diplomacy efforts and challenged pro-coal interests. Two years on from the Paris Agreement, President Trump claimed he was going to ‘bring back coal’. The creation of the PPCA showed that other governments were prepared to push coal to the exit and deliver on their Paris promises.

When the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015, the UK was the sole national government to have committed to phase out coal power generation. Coal was the dominant source of electricity production globally, while the pipeline of proposed new coal construction was still growing.

Through the creation of the PPCA and the combined influence of governments, civil society campaigns, and market forces, coal’s grip on global electricity systems has loosened. In 2019 UN Secretary General Guterres would begin his repeated call for ‘no new coal’. Under Alok Sharma’s leadership, the UK COP26 Presidency has positioned Glasgow as a moment where governments can step forward with contributions that help ‘consign coal to history’.

The end of new coal construction is in sight

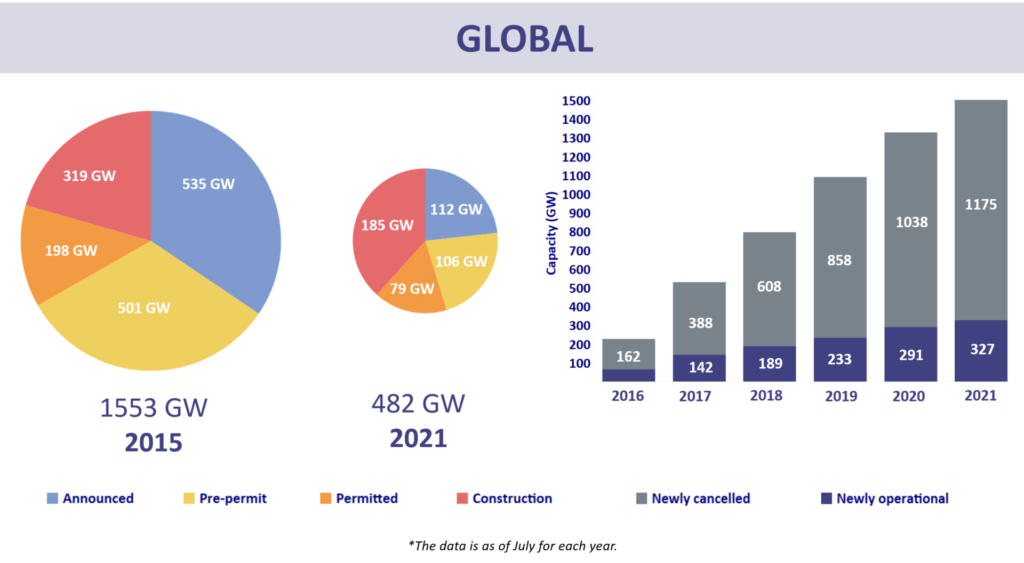

The terrible economics of coal are reflected in increasing political momentum. The global pipeline of planned coal projects has collapsed by 76% since 2015 as countries recognise that new coal construction is a bad idea on economic, social, and environmental grounds. 84 countries that previously considered building coal are now heading for coal-free futures, while the list of countries still considering coal dwindles by the day.

2021 has also seen public international coal finance finally dry up, removing the crucial financial support that kept the prospect of new coal alive. Xi Jinping’s September announcement that China would no longer build coal abroad is one of a wave of similar commitments including South Korea and Japan earlier in 2021; the G7’s agreement to end coal finance this year; and last week’s OECD agreement to no longer finance coal through Export Credit Agencies. The recently launched No New Coal Power Compact provides a platform for governments to confirm their progress and focus on the clean alternatives to coal, through COP26 and beyond.

Coal phase out is gathering pace

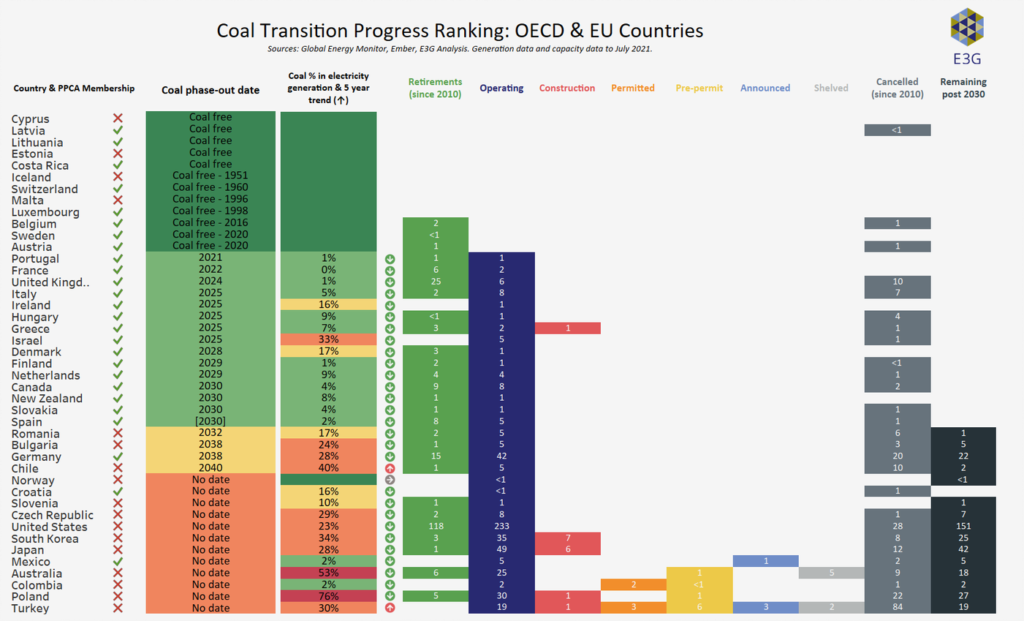

Rapid progress is also being made on closing existing coal plants fast enough to keep 1.5 alive. 60% of OECD and EU countries are already members of the PPCA. 56% of OECD coal capacity has either closed since 2010 or is scheduled to close by 2030. Germany’s mooted 2030 coal exit date would take this to 58%. If US plans for a carbon-neutral energy system by 2035 are to become a reality they would need to quit coal by around 2030, taking this to over 80%.

COP26 offers a space for this coal exit dynamic to be extended to non-OECD countries, through the launch of coal retirement mechanisms and dedicated funds that can support power plant retirement and a Just Transition for workers and communities.

China in the spotlight

Meanwhile, China is increasingly under international and domestic pressure to apply its shift on overseas coal-to-clean at home. China’s current energy crunch is a result of a mismatch between increased electricity demand and a shortfall in coal supply, made worse by price controls and inadequate market signals. These are short term problems. China already has an overcapacity of coal power plants and policymakers know they need to improve market functioning rather than building more new coal plants. Chinese policymakers know that they need to properly price the costs of coal, including pollution and CO2 impacts. Doing so would reduce new coal construction and accelerate the retirement of existing power plants.

Coal exit is now a leaders’ level topic

As we head into COP26, the world of coal is a hugely different place to that of 2015. The significant momentum built in recent years was turbocharged in 2021. Coal is on the international climate agenda in a way that it has never been before. “Coal, cars, cash, and trees” are the quartet of real-world deliverables the UK is asking governments to progress, alongside the core COP negotiations. The G7 and G20 have both seen coal exit elevated to leaders’ level discussions for the first time ever.

COP26 provides a milestone moment to pause and look back at how far the coal transition has progressed. The way ahead is now generally downhill, but with some major obstacles remaining. Coming out of Glasgow it will be clear who is willing to accelerate towards a coal-free world and who is yet to get on the right side of history.