The EC is currently considering a mission proposal to achieve “100 climate neutral cities by 2030 – by and for the citizens”. Arguing for its endorsement and the proposed umbrella governance, Simon Skillings and Eleonora Moro at E3G explain why cities are an ideal laboratory for tackling the big unanswered question: which European Green Deal (EGD) pathways will win genuine public support. No one should doubt that the EGD will be disruptive. So without the public behind it, and fast, it risks stalling.

City authorities are closer than most to the public, on the front line, and continuously delivering a wide range of projects and services while doing their best to make sure ordinary people recognise the benefits and are incentivised to act. Each city will uncover different solutions to its decarbonisation challenges. The best solutions can be taken up by others. But knowledge sharing between cities, national governments and the EU is thin. An overall governance process is sorely needed. That process must be flexible and responsive with its financial support and regulations as new solutions and obstacles materialise. The major constraints will be the necessary EU and national-level decisions on standards, regulations, infrastructure and funding. The authors reference a 9-city case study already underway in Sweden.

The umbrella governance provided by the proposed cities mission provides the best chance of driving forward the innovation that is required for climate neutral cities and, importantly, creating the better future to which everyone in the EU can aspire.

People sit at the heart of the European Green Deal (EGD). It is about creating a better and inclusive future for everyone in the EU. We cannot expect them to make the changes necessary unless they believe their lives will improve. The EGD will only be successful if the changes are widely supported.

Unfortunately, there are many areas where achieving the necessary support will be challenging, as the transition will impact the daily lives of everyone. For example, the energy system transition requires that people must upgrade their homes to improve energy efficiency and install zero carbon heating. This is likely to be expensive and disruptive, and people are often quite happy with their existing situation. Shifting to climate neutral modes of transport in cities will give rise to similar issues.

We do not yet know how to make the EGD publicly acceptable

The EGD needs this equation to shift – both through changes in mindset as well as innovation in technology, business models, and financing schemes. It is necessary to make zero carbon solutions more attractive to people, and to do so within the next decade. This is a problem that we do not know how to solve, and it represents one of the key innovation challenges for the EU.

The role of Cities

Cities have a key role in solving this problem, since they are the governance level that has the best understanding of local people’s needs. City authorities are also urban planners and service providers, and their local policies can encourage greater uptake of sustainable solutions, setting a trend for the national level.

Decarbonising Cities

Many cities and local regions across the EU have set ambitious targets to achieve climate neutrality and this, amongst other things, requires refurbishment of the built infrastructure. Ingenious individuals and organisations are already exploring approaches to solve this challenge, often supported by EU or national funding and knowledge-sharing initiatives.

However, the current approach requires local and city authorities to be highly proactive, despite often being constrained in their capacity to address these issues. There is no overall governance process that is driving progress towards the goal of decarbonising EU cities, capturing and sharing successes, and ensuring action is taken to tackle the problems that emerge. Innovation in cities is currently a random, bottom-up process which is not directed towards achieving the goals of the EGD.

EC “Innovation Missions”

Fortunately, there is the opportunity to correct for this deficiency. The European Commission is currently considering proposals for ‘innovation missions’, developed within the Horizon Europe research and innovation framework. These include a proposed mission to achieve ‘100 climate neutral cities by 2030 – by and for the citizens’. This proposal has been carefully constructed by a ‘Mission Board’ to deal with the diversity of contexts across the EU, focusing on achieving real progress by 2030, through inter-city exchange and supporting city access to sources of funding. Moreover, it recognises the centrality of individual interests, involvement and the requirement to understand and meet their needs.

Communication between cities, national authorities and the EU

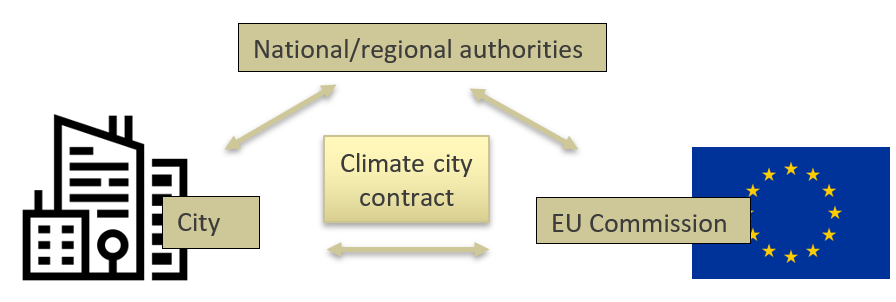

The proposed mission for cities is valuable because it provides a governance framework that is flexible to respond quickly to emerging lessons, with the potential to enable two-way communication between cities, national authorities and the EU level, as well as channelling public funding to where it is most valuable.

A ‘climate city contract’ would sit at the heart of this process, governing these important interactions (see chart below based on cities mission board proposal).

Case study: Sweden

Cities across the EU have already called for this proposal to be endorsed by the Commission, thereby highlighting that it would be plugging an important gap in delivering net zero. Indeed, Swedish cities and government agencies have implemented a similar approach at national level in recognition of the value it can create. Nine Swedish cities have signed-up and have committed to work to reduce emissions, increase their innovation capacity, and involve their citizens in the process. In return, the government agencies will review laws and regulations and create a platform that makes it easier for municipalities to fund initiatives.

We need flexible, responsive financial support and regulations

The climate neutrality transition cannot be achieved through bottom-up innovation within a framework of financial support and regulatory rules that is not flexible to respond quickly to emerging lessons.

A new consumer deal is required which inspires and incentivises people to act because they believe it will make their lives better. It must be easy and convenient to make the necessary changes and this requires excellent support and service. It must be flexible to local and individual circumstances, which means there must be choices available. Above all, costs must be fair, and people should certainly be no worse off.

Constraints: EU and national decisions. And funding

The choices presented to energy consumers will not only be constrained by a framework of standards and regulations (e.g. phase-out dates for fossil gas-fired domestic boilers) but by big infrastructure decisions taken at EU and national levels.

Replacing fossil fuels will require considerable upfront investment in networks, production facilities and processes, appliances and building fabric. Where the funding comes from and who ultimately pays will be central to the new consumer deal and to ensure a socially just transition.

For example, green hydrogen produced from renewable electricity is likely to be a scarce, high-value commodity that will not be widely available for domestic heating. No ‘silver bullet’ solutions will apply to all city contexts and an interactive two-way process is required to inform cities about where it is useful to explore hydrogen solutions and where alternatives such as electrification are more promising. This is a conversation that must be co-ordinated across the EU.

Replacing fossil fuels will require considerable upfront investment in networks, production facilities and processes, appliances and building fabric. Where the funding comes from and who ultimately pays will be central to the new consumer deal and to ensure a socially just transition.

Public funding will be important, at least in the early stages of demonstration and piloting, but mass deployment requires that the heavy lifting must be done by private finance. It is not possible to define the regulation and market rules that will simultaneously deliver a reasonable return to investors and a good deal to citizens without trialling and testing innovative approaches in various real-world city contexts. It is difficult to imagine how this might be achieved without an overarching governance process that is able to channel public funding where it will be most valuable and provide an interface with regulatory authorities to facilitate innovation in market rules and regulations.

Achieving the objective of 100 climate neutral cities by 2030 is certainly ambitious, but it is the level of ambition that is required to deliver the goals of the EGD. The umbrella governance provided by the proposed cities mission provides the best chance of driving forward the innovation that is required and, importantly, creating the better future to which everyone in the EU can aspire. The European Commission should endorse this proposal and allow the valuable work to proceed without delay.

This article originally appeared in Energy Post.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash.