The plan to create a ‘Clean Power Alliance’ was one of the boldest commitments in the Labour manifesto. The new UK government should create a high-profile ‘umbrella’ platform to leverage the ecosystem of existing energy transition alliances. This platform would bring political leaders and first movers together, securing ambitious commitments and ensuring their implementation.

The proposed Clean Power Alliance (CPA) has become a core part of Labour’s foreign policy platform, touted as a way to position the UK ‘at the very heart of the single most significant technological challenge and opportunity this century’.

The alliance has been billed as a ‘reverse OPEC’, with members (expected to decarbonise their power systems by 2030) collaborating on supply chains and grids to keep energy prices low, much as OPEC countries conspire to keep oil prices high.

But if the CPA is only open to countries with 2030 power sector decarbonisation targets, it will inevitably become a narrow group of rich nations. There is a risk that, to the rest of the world, such an alliance would look remote and out of touch.

To drive forward the energy goals agreed at COP28, the CPA should be engaging all countries, particularly those where the greatest impact on global emissions can be achieved – major emerging markets and developing economies like Indonesia, India, Nigeria and Vietnam.

Maximising the impact of the existing energy ecosystem

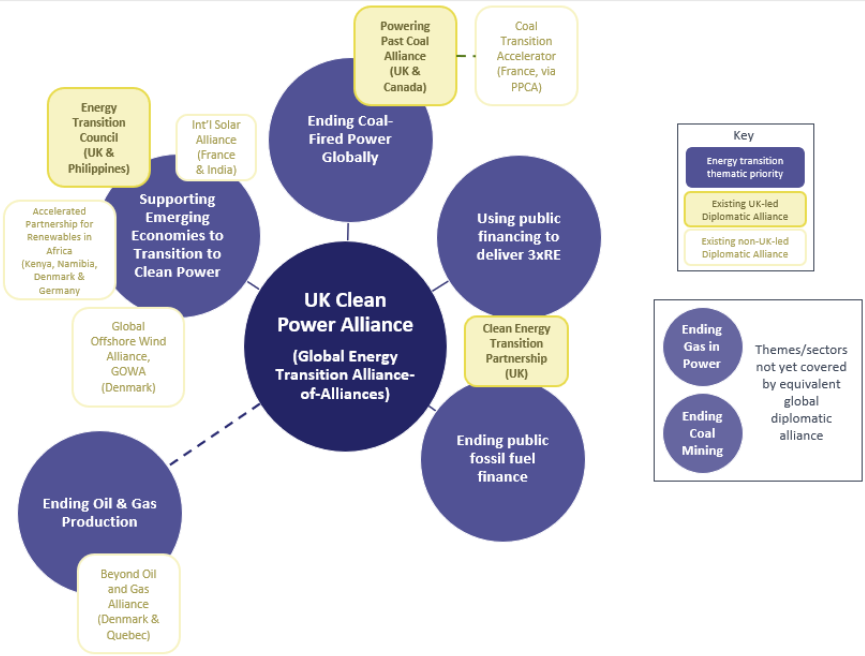

Creating a CPA from scratch to drive global power sector decarbonisation would be unnecessary and counterproductive because the UK already sits at the heart of several diplomatic alliances dedicated to catalysing the global energy transition.

- The Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA), founded by the UK and Canada at COP23 in 2017, has been hugely successful, growing from 27 to 181 national, sub-national and non-state actors committed to the phaseout of unabated coal power.

- The Energy Transition Council (ETC), launched by the UK during its COP26 Presidency, provides political, financial and technical advice to more than 40 governments and institutions in the power sector.

- The Clean Energy Transition Partnership (CETP) has the power to shift $28 billion into clean power annually through its current membership alone.

Today, the UK is co-chair or chair of all these alliances. Were the UK to join the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA), the Labour government would have access to a comprehensive set of energy transition initiatives, from ending coal power (PPCA), phasing out oil and gas (BOGA), building out clean power (ETC) and shifting the finance to back it all up (CETP). These networks combine strong, pre-existing civil service expertise and deep networks in developing countries.

Despite their successes, these alliances suffer from a lack of high-level political attention, and, just as significantly, an absence of deliberate coordination.

The CPA doesn’t need to re-invent the wheel – it can make an immediate impact simply by addressing these gaps. Coordination should extend to non-UK-led alliances, such as the Global Offshore Wind Alliance (GOWA), Accelerated Partnership for Renewables in Africa (APRA), and International Solar Alliance (ISA), working closely with key allies like Germany, France, Denmark, Sweden and India. Engaging with the wider ecosystem would also demonstrate the UK’s international convening power.

Merging this network into a single, monolithic alliance is an option, but this would be a mistake. Part of what makes institutions like BOGA and the PPCA so successful is their flexibility. Having several alliances with different objectives allows nimble, high-ambition coalitions of countries to form, coordinate and share technical expertise around specific issues.

The CPA should act as a high-profile ‘umbrella’ platform for these groups. It should bring political leaders and first movers together to drive the global energy transition, secure ambitious commitments and ensure their implementation. It would also provide a venue for the alliances to coordinate at a working level, for example on outreach to countries on NDC preparation.

The following diagram shows what a Clean Power Alliance, constituted on this model, could look like:

Injecting political momentum

After setting out a vision for the CPA, the new government should inject the alliance with political momentum by proposing to host a Clean Power Ministerial in mid-2025. The CPA should feature prominently in the Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary’s speeches at the UN General Assembly and be a core part of UK diplomacy at COP29. Outreach and engagement with allies, particularly those leading other alliances like BOGA, will be essential.

Next, the government should bolster the capacity and coordination of these networks. This should be done by supporting and aligning teams in DESNZ, the FCDO and at post in key countries, as well as empowering network secretariats. Finally, the government should ensure there are ongoing channels through which these alliances can coordinate their outreach to target countries.