Over the past five years, the EU has been at the forefront of bringing sustainability into financial regulation and has been building a sustainable finance architecture to achieve the transition to a sustainable economy. Three pieces of regulation are the pillars of this framework: the EU Taxonomy, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) which replaced the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) in 2023. Together, they assist investors in identifying sustainable activities and investments by requiring companies to disclose sustainability information.

In this blog, we look at data and trends to consider the implementation of these regulations on the ground. While there are several challenges to address, by tackling regulatory inconsistencies we can establish a more coherent policy framework that will redirect financial flows to both green and ‘transition’ activities, enabling an orderly transition in the European market.

What does the data say?

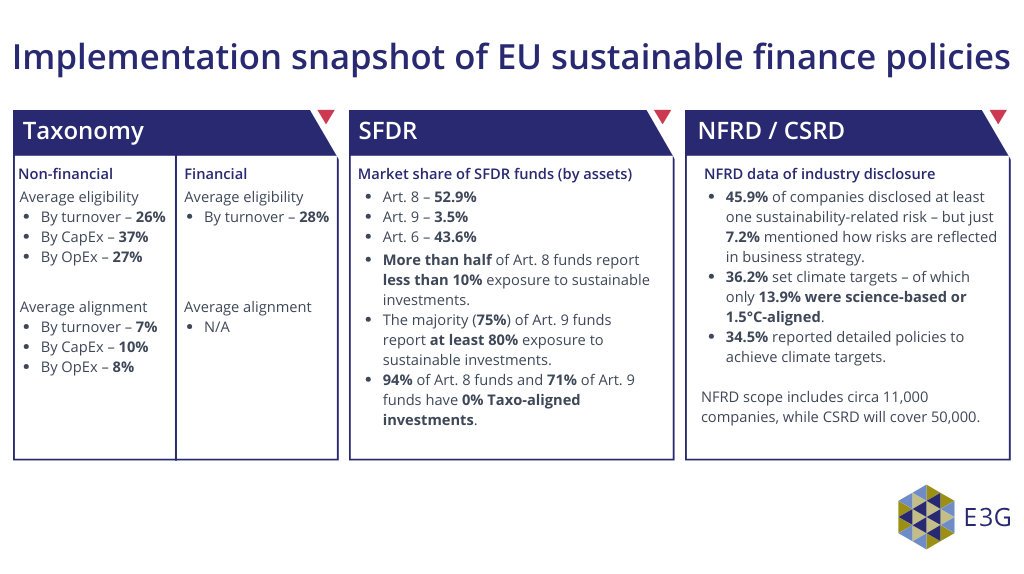

The snapshot of data reported through the Taxonomy, SFDR, and NFRD below shows that European companies and financial institutions are not currently demonstrating high levels of alignment with the current regulations.

The data points to several issues:

On average, only a quarter of a company’s activities are considered Taxonomy-eligible, less than 10% of which are Taxonomy-aligned. Coupled with the very low percentage of funds that have sustainable investment as their primary objective under the SFDR (Article 9 funds), this suggests there are few economic activities considered green in the EU market. For corporate reporting, NFRD data shows that few companies are providing sustainability information, and even less disclose detailed data.

While there has been sustained demand for sustainable investment since the entry into force of the SFDR, there is a lack of clarity around products being sold as green. Article 9 funds have a high exposure to sustainable investments but most of these funds (71%) have 0% Taxonomy-aligned investments, pointing to issues with the definition of sustainable investment, which also raises the risk of greenwashing (misleading claims about a product or service being ‘green’).

Sustainability related risks are not being managed by companies, with only about 7% of all those who disclosed at least one such risk reflecting them in their business strategy. Also concerning is the data on climate targets: only 14% of reported targets are science-based or aligned with the Paris Agreement goal. If the taxonomy was more explicitly linked to reporting – which is on the horizon with the CSRD – companies could address this by using it for measuring progress within a strategic plan to reach a science-based target. Taxonomy criteria for adaptation could also be used to support climate risk management.

Tackling the regulatory uncertainties for a coherent sustainable finance framework

Where do these findings leave us? Greater coherence in the regulatory framework between the three regulations can partially resolve the existing challenges. Key recommendations are to:

- Specify minimum thresholds of Taxonomy alignment that Article 8 funds (those with sustainability characteristics) and Article 9 funds (those with sustainability as a main objective) need to be considered partly or predominantly green;

- Establish a uniform definition of sustainable investment criteria for financial products under SFDR; and

- Harmonise corporate financial and sustainability reporting between different regulations by closely aligning disclosure requirements under CSRD and SFDR, to plug information gaps.

The SFDR consultations launched by the European Commission in September are a positive step to engage on several of these issues.

More broadly, however, current low levels of green activities and financial products point to the need to incentivise more transition finance. This is financing for activities that are not yet green but in the process of becoming green, and for activities that support whole-of-economy transition, innovation and phaseout of unsustainable assets.

The EU does not yet have a robust transition finance framework in place that would help steer finance towards such activities. Transition planning has emerged as an important tool in this regard as companies are already implementing such transition plans on a voluntary basis. However, in the absence of a common methodology and rules, only 5% of companies disclose sufficient information to demonstrate the credibility of their transition plans.

Both the rising demand from investors for ESG information, and companies estimating that climate-related opportunities outweigh the risks, paint a clear picture: there is an underlying economic advantage in transitioning towards a sustainable economy. Regulatory requirements for transition planning are emerging in various EU rules in the making (e.g., ESRS, CSDDD, CRR/CRD). Yet, similarly to the current sustainable finance regulations, consistency between these rules and within the broader EU finance agenda will be key to boosting European businesses’ competitiveness and supporting their transition.