The European Commission’s assessment of the role of natural gas in draft National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) is inconsistent with its own climate targets.

As European Energy ministers discuss national plans, they should ensure a consistent approach will be taken across the 28 draft plans.

The European Union’s long-term climate objectives imply the Union has to phase-out use of unabated natural gas almost entirely by 2050. Our analysis of selected current trajectories and draft NECPs suggests Member States are steering the Union towards a glut of natural gas. Wasted investments and a tottering and costly energy transition may be the result – and the Commission is turning a blind eye.

A lack of Member State plans for the transition away from natural gas undermines the Union’s climate objectives

The trajectories drawn in the selected draft NECPs are not aligned with European ones to achieve 2030 and 2050 climate objectives. This is concerning as the countries analysed (Bulgaria, Germany, Italy, Poland, Romania) makeup nearly 40% of the EU’s current annual gas consumption.

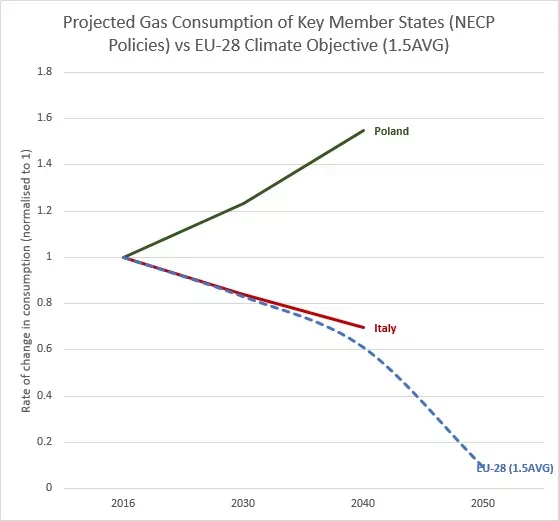

Business-as-usual trajectories are disconnected from what the Commission considers could be two scenarios “compatible with 1.5 degrees”, included in the Clean Planet for All communication. According to this document, gas consumption is set to decrease by 3-4% (figure 1). Without explicit plans to address this gap – or without other Member States compensating for them – these five countries alone put climate targets at risk.

Only a few Member States explore the impact of policies on energy consumption (out of those analysed only Italy and Poland do). The lack of detail makes a proper analysis of the gap difficult (cf figure 2). Many countries, instead, plan to expand national gas infrastructure:

- Germany is planning to expand and restructure the long-distance gas network. In the period 2016-2026, the plan for gas includes 113 measures and building an additional 848 kilometre long interconnector.

- Romania plans to invest €145 million on the gas transmission system in 2018 alone and outlines nine major gas projects to be developed until 2027, the majority concerning the connection to new sources rather than improving market integration.

- Italy is seeking to expand its LNG import infrastructure and domestic infrastructure for gas use in transport.

According to an internal document by CAN Europe, eleven[1] Member States are planning to increase their gas infrastructure capacity and five[2] countries want explicit extraction of resources.

Member States should be planning future investment based on the most likely future and, considering ongoing negotiations at the EU level, this future is likely to be climate-neutral within a few decades.

By the end of 2019, EU governments will have to submit a revised and final version of their plans, taking into account the Commission’s recommendations. The Commission should require Member States to include a strategy aiming at phasing-out unabated natural gas from national energy systems before 2050, to bring the decarbonisation of the energy system in line with a realistic decarbonisation trajectory for the European Union’s economy.

The Commission’s assessment of natural gas is inconsistent across plans

The Commission’s recommendations on the draft NECPs aim at improving the quality of the final plans that Member States must submit by December 2019. In some cases, the Commission pointed out inconsistencies between climate targets and planned natural gas investment by Member States.

In the Italian NECP, for instance, significant investments are planned in the gas sector, making it a vital element of the national energy system in 2030. In its assessment, the Commission asked for clarification over the compatibility of the development of the gas sector with national decarbonisation objectives.

The Romanian NECP also outlines significant investments in the gas sector until 2030. It plans to continue exploiting national energy resources to diversify the country’s energy mix. Romania is also planning additional gas distribution infrastructure to reach isolated communities and economic players. In this case, the Commission’s recommendations do not point out the inconsistency between Romania's planned policies and decarbonisation objectives. Instead, the Commission is even suggesting eliminating “undue restrictions to investments in gas production considering the regional potential of the reserves in the Black Sea” – with the risk that much of this will find little upake if climate policies are implemented.

Country specific circumstances matter, but the European Commission must be consistent when assessing the countries’ NECPs. Only a clear signal over what sources of energy are compatible with modernisation and decarbonisation of the Union’s economy will allow the EU to rise to the investment challenge. The comments on the Italian draft plan indicate that the Commission considers a policy of cementing and expanding natural gas dependence is inconsistent with decarbonisation targets. The same approach must be used with other countries planning for a similar expansion to ensure fair and balanced contributions towards climate goals from all Member States.

The EU’s own policies send inconsistent signals over the future of natural gas

Member States are not the only ones who should revise their energy system planning in order to guarantee compatibility with EU climate targets. European institutions – and in particular the European Commission – must address inconsistencies among different pieces of legislation, especially when it comes to infrastructure investment. What we build today will have effects for decades to come and therefore, a direct impact on the Union’s credibility to meet the climate neutrality goal.

The Trans-European Network (TEN-E) regulation sets the guidelines to select infrastructure projects eligible for European funding under the Connecting Europe Facility. The 2013 TEN-E legislation is now outdated: it disregards the latest policy developments of the Union, from the adoption of the Paris Agreement to the Energy Efficiency First principle as defined in the 2018 Governance regulation. This policy inconsistency not only undermines the political leverage of the European Commission towards Members States but also sends misleading signals to private investors.

The European Commission is required to evaluate the TEN-E regulation by the end of 2020 in light of its decarbonisation commitments. This process is even more relevant with the upcoming European Green Deal that will be released by the new Commission within the first 100 days of its mandate. This is an excellent opportunity to make sure the Union’s tools are truly compatible with broader policy framework – the draft energy lending policy of the European Investment Bank and the proposed Sustainable Finance taxonomy are good examples to follow.